Mines are one of the most unsafe working environments. Miners often have to deal with toxic gases, the risk of explosions and collapses, as well as chronic illnesses from breathing the dust. While many safety regulations are dictating how mines must be built and managed to protect their workers, it won’t be a surprise if you visit a mine and notice workers putting themselves in danger. Over time, the managers and inspectors often start ignoring minor violations for the sake of convenience. The safety of workers may be compromised leading to a disaster.

Darby Mine No.1 Disaster is an example of small overlooked safety violations that led up to an explosion that killed and injured workers.

Background: Darby Mine No.1

The mine was located in Kentucky and operated by Kentucky Darby, LLC under contract with Jericol Mining, Inc of Tennessee. The LLC was owned by three individuals including Ralph Napier, who was the superintendent and the person in charge of health and safety at the mine at the time.

The Darby Mine No.1 was located underground and began production on May 28, 2001, using the room and pillar mining method. The production was in the Darby coal seam which was below the Owl coal seam and the two were mined together at various locations. The resulting mining height varied between 40inches and 144 inches.

To ventilate the mine, a single belt-driven exhaust fan powered by a 100-horsepower electric motor was installed at the surface. After the accident, the investigations suggested that the fan was removing 114,206 cubic feet per minute of air at a pressure of 3.2 inches of water. According to records from the last health and safety inspection at the mine, methane was being liberated from the mine at a rate of 38,707 cubic feet daily.

The mining in the A Left Section in which the explosion occurred started in late October 2005. Two months before the accident, the company had completed mining in this section. And they had built three seals made of Omega 384 blocks to seal off the worked-out area.

For the most part, miners moved within the mines using a battery-powered personnel carrier.

The day before the incident, the weekly site inspections were carried out by the mine examiners. They inspected the seals visually and measured the presence of methane using a handheld device. At this point, the area was deemed safe by both the personnel, and methane concentration was measured to be at 0.1%.

The accident

The accident happened on the early morning of May 20, 2006, at around 1:00 AM. There were six miners part of the midnight crew were in the mines at the time of the accident.

At the beginning of their shift at 11:00 pm, two members of the midnight crew headed straight to the workers’ section. Two others went on a separate way to inspect the conveyor chain that had broken earlier that day. They were met by the belt attendant there.

At around 12:45 AM, everyone except two of the afternoon shift crew went to the surface. The two remaining personnel were tasked with removing the metal straps next to the seals of section A. These metal straps were used to support the roof earlier but were not necessary anymore.

These two personnel from the afternoon shift loaded a personnel carrier with oxygen and acetylene tanks, a cutting torch, and other tools for the task and headed to the seal. While they had methane detectors on them, the investigation after the incident suggested that they were never used, even though it was functional. And there’s no evidence that they performed any other tests to check for methane.

The explosion was triggered when the acetylene torches were used in the presence of methane. The coal dust in the mine may have contributed to the problem. After the afternoon crew exited the mine around 1:00 AM, they were buffeted by a sudden gust of air, debris, and dust from the mine portals.

The midnight crew within the mines away from the explosion heard the sounds. The foreman gathered the crew together and they boarded two personnel carriers to head to the escape way. They donned their self-contained self-rescue or SCSR suits when they encountered smoke along the way.

When the personnel carried got lodged in the debris the crew decided to proceed further on foot. According to survivor accounts, two of the crew members removed their protective suits somewhere around this point to discuss the next course of action. But they didn’t have detectors on hand that could sense the presence of carbon monoxide.

They decided that one of the crew members would follow a high-voltage power line to the surface. This crew member was the only survivor and this was the point at which they last spoke to the other miners.

Rescue

The survivor walked for a while but then collapsed and lost consciousness. When he regained consciousness he crawled a bit further and was later found by rescuers.

The other three in this group were found to be dead from carbon monoxide poisoning at different locations in the mine.

The two crew members working with torches were found next to the seal killed by the forces from the explosion.

The local MSHA officials were informed of the incident soon after the explosion and they took the carbon monoxide readings at the fan as soon as they arrived. The handheld detector found 2.6% methane and 500ppm carbon monoxide and confirmed fire or explosion.

The rescuers decided to travel barefaced through the mine to find the miners until they detected carbon dioxide concentrations of more than 50ppm. The team periodically checked the carbon monoxide concentrations using a handheld detector.

Around 3 AM they found the lone survivor with his SCSR donned but without goggles or a nose clip. He was transported to the surface with the help of a personnel carrier.

The team established a fresh air base in the mine at a location just before where high levels of carbon monoxide were detected. But attempts to move this forward were unsuccessful.

Later investigations revealed issues about the rescue process itself — it was noted that it didn’t follow accepted practices and while the goal was to get the miners out as soon as possible, it put the rescuers in danger.

While the team used radios, there were lapses in communication between them and the command center. Even when one of the miners was found, no communication was recorded between the team and the command center. Nor was the high concentration of carbon monoxide reported.

Rescue workers also put themselves at high risk when they proceeded out of the fresh air base before the backup rescue teams arrived. If the rescue team themselves faced difficulties, the casualties would have been higher.

What could have been done to prevent the accident?

From the incident reports, it’s pretty clear that the mine didn’t have proper safety practices.

For starters, the explosion was caused by improper handling of the acetylene torch. The crew didn’t measure the methane levels before using it. The fact that the crew had a methane detector but didn’t use it indicates the lack of a proper safety culture. Perhaps the crew wasn’t properly trained in the use of these tools or perhaps safety regulations were routinely ignored.

Either way, the incident reflects that safety wasn’t given sufficient priority there.

Another aspect of this is with the SCSR suits. The employees were provided the suits and they did don the suits as soon as they confirmed dust and explosion. But they removed the suits in between without checking the environment properly. From the post-incident reports, it is clear that the employees weren’t trained to wear the suit properly. They were found without nose clips and goggles.

While the crew had methane detectors, they were not provided with carbon monoxide detectors. While we cannot know for sure, carbon monoxide detectors may have prevented the death of miners who were not injured in the initial explosion.

The incident could have been prevented and the casualties mitigated to a large extent with proper training for the miners. Operations could have been made significantly safer had the miners been provided with adequate tools.

Mines could also have used checklists for different procedures. For example, when they were going to use certain equipment, they could have checked off items in a checklist to make sure they haven’t missed any steps. In the case of the acetylene torch, they could make sure that tubes are in working order, that there’s no methane in the atmosphere, and that the controls are working well before using it.

They could also have used tracking systems within the mine. As noted in the incident reports, rescuers were unable to locate all the victims quickly. By implementing an RFID or NFC tracking system, the crew could have kept track of each other. And the rescue teams could have found them much faster.

Best practices for mine safety

Here are some of the top safety practices that can help prevent accidents in mines.

Use checklists

Checklists ensure that even if the same task is performed many times by the same person over a long period, the safety protocols are followed to the dot. It prevents confusion on whether a task was performed or not, and it keeps a record of safety practices.

Conduct regular walkarounds

Regular walkarounds ensure that all the equipment is properly functioning. It ensures that the safety devices are primed to work in the event of an accident. It can help detect safety issues early and take preventive measures before any accidents occur.

Keep track of miners

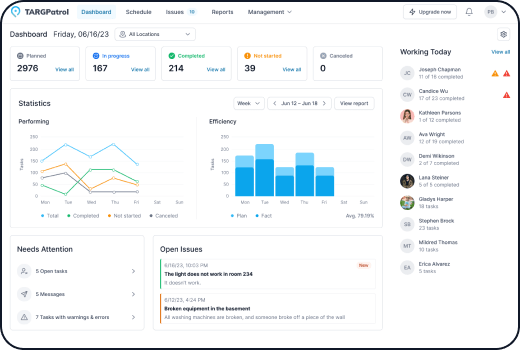

Keeping track of miners helps early rescue in case of any accidents. It helps ensure that the miners are completely cleared off from any area before any dangerous procedures are performed. While GPS tracking may be difficult, companies can use RFID or NFC tags to keep track of employees with tools like TargPatrol.

Train miners on proper security protocols and using equipment

Make sure that the equipment operators are properly trained and aware of emergency procedures. Even if they’re certified, make sure they get regular training to update their skill set and help them respond quickly in the event of an accident. Ensure that employees know the proper procedures if they face any safety issues.

Build a safety culture

A safety culture brings a sense of responsibility for miners toward their safety. Instead of making them follow rules and regulations, a safety culture brings out initiatives from the workers themselves. It makes them prioritize safety and motivates them to stay safe.